Hi all,

I have a series of questions about IRFs. Maybe, they are basic questions but I have not found answers yet. Any help is very well appreciated! Thanks!

Q1.

Should we always interpret IRFs using solely the equilibrium equations of our model or we can mix that with economic intuition (that may not be explicitly captured by the equilibrium equations of our model).

For example, from the equilibrium equations of a simple RBC model (with only ricardian households), an increase in aggregate labor supply and aggregate consumption (after a productivity shock) is well captured by the equilibrium equations of the model, and this is also seen in the IRFs.

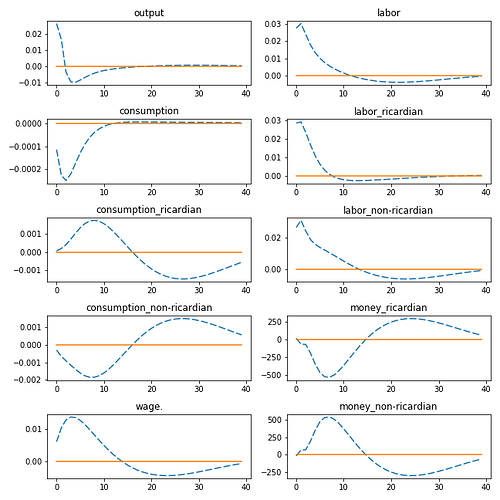

In complex models (with both ricardian and non ricardian households), however, Celso Jose Costa Junior (chapters 6 and 7) explains that the response of aggregate labor supply and aggregate consumption (to productivity shock) depends on income and substitution effects as ricardian and non-ricardian households respond differently (in an opposite fashion). Ricardian households increase labor supply and reduce consumption. Non-ricardian households, on the other, reduce labor supply and increase consumption. On aggregate, labor supply falls, and aggregate consumption increases (which is in contrast to simpler models (chapters 2 and 3) with only ricardian households where both aggregate consumption and aggregate labor supply increases after a productivity shock).

While the IRF explanations in the book make sense, income and substitution effects are not explicitly captured by the equilibrium equations of the model. In this case, it appears to be more of an economic intuition to help explain the IRFs. Thus, why ricardian and non ricardian households respond differently to productivity shock.

So it is not like, ricardian households will always reduce consumption (chapters 6 and 7) or increase consumption (chapters 2, 3, 4) after a productivity shock (see, Junior, C. J. C. (2016))

Given the above, my understanding is that, if we can find sound economic intuition to help explain the IRFs, then we are fine even though that intuition may not be strictly captured by the equilibrium equations of our model (for example income and substitution effects). Nevertheless, some IRFs like output response to productivity shock is kinda standard, I guess.

Q2.

Here is my 2nd question. Given that aggregate labor and aggregate consumption (among others) may go either way after a productivity shock (for example, in models with ricardian and non-ricardian households), should we change values of structural parameters or adapt our model in a way such that the model is consistent with the economy we are trying to build the model for? In relation to my first question, this will be, for example, by adjusting the proportion of ricardian and non-ricardian households depending on whether we want a procyclical aggregate labor supply or a countercyclical aggregate labor supply after a productivity shock.

I am sorry for such a long question.